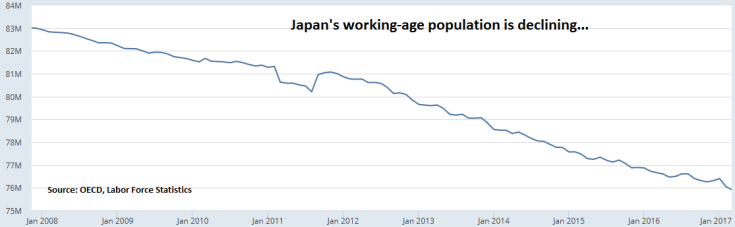

Japan’s population is shrinking. Perhaps more worryingly, Japan’s working-age population is shrinking even faster: after reaching a peak of 87 million in 1997, the number of those aged between 15 to 64 stood at 76 million at the end of 2016. Few babies are born and students graduate at an older age. More are retiring. The number of foreign workers has increased marginally over the years, but is not expected to rise significantly anytime soon.

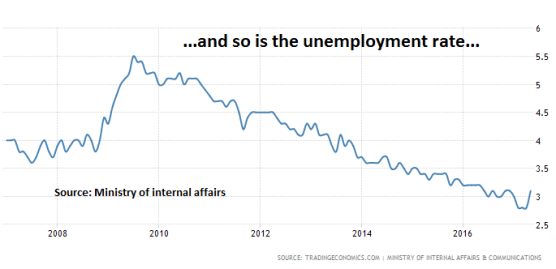

As a result, those that are still part of the workforce have little difficulty finding a job. The unemployment rate now stands at less than 3%, the lowest over the past two decades. Across Japan, there are on average 1.48 job openings for every applicant, the highest since 1990. Although there is stiffer competition to join some of the large firms, overall Japanese workers are spoilt for choice.

In most countries, such low unemployment rates would increase wages. As there are plenty of jobs available, workers will want to negotiate better terms for themselves.

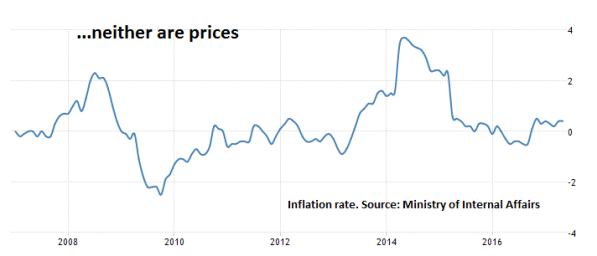

Increasing wages is seen as a way to boost domestic consumption: if workers earn more, they should also spend more. If they spend more, the price of goods and services sold in the country should increase. Rising inflation would allow Japan to free itself from a deflationary mindset which has plagued its economy for the past 25 years: as consumers expect prices to decline, they postpone their spending.

That’s the theory anyway. Higher wages do not always lead to higher consumption, although they often do. The deflationary mindset, popular with Western observers, ignores the fact that according to regular surveys by the Bank of Japan, two thirds of households expect prices to rise over the coming year; 80% expect those prices to rise in the next 5 years. So it is unlikely that households limit their consumption in anticipation of falling prices. Probably a better explanation why Japanese families are not spending a higher portion of their income has to do with a strong aversion to risk. A VAT increase in 2014 did little to help.

But even if raising wages does not necessarily lead to more consumption and higher inflation, it should still be pursued as an end in itself. The ultimate aim of managing an economy isn’t an endless pursuit of higher production or productivity, it is about raising the living standards of its people, and increasing (inflation-adjusted) wages plays an important role in fulfilling that objective.

Inside the Japanese labor market

The problem in Japan is that despite record low unemployment, wages are not rising. Although there has been a slight pickup in the past few months, real wages have been stagnant for the past 20 years. In March 2017, some of Japan’s top companies including Toyota and Panasonic announced their lowest annual wage hikes in years.

Why don’t workers shift between employers in search of higher pay when there are so many jobs available? To answer that question, we need to delve deeper into Japanese corporate culture.

The job market in Japan is much less dynamic compared to most developed economies. The job-for-life system, threatened by retrenchments in the 1990’s, is still the expectation for most Japanese workers. Many firms continue the long-standing practice of hiring mostly new graduates and employing them until they retire.

In such a system, workers develop a strong bond with their colleagues and employers over the years. Job security in risk-averse Japan is more highly valued than salary increases. Members of a social group will favor harmony and unity over their personal interests, sometimes at the expense of individual achievement. This is quite similar to the sense of togetherness or gemenskap that we discussed in the case of Sweden, but it goes further than that. Those who break that harmony by seeking work elsewhere will be negatively perceived; in fact, many would feel a sense of shame abandoning their colleagues. Salary increases and bonuses are often applied to a group rather than an individual, further discouraging the individual from leaving the group.

Those few workers who do leave their job very rarely do so because they were unhappy with their wages. When they apply for a new role, compensation will hardly ever be mentioned or negotiated. That, again, would convey a negative impression.

Such concepts may seem alien to non-Japanese people, but they play a big role in shaping the local workplace.

An important structural change that occurred since the mid-1990’s is the increased reliance on ’non-regular’ or temporary workers, which today make up more than a third of the workforce. This trend started when firms, faced with declining productivity, sought to reduce labor costs and hire workers during temporary increases of activity. Those often relate to jobs with low qualifications, are mostly filled by women or retirees and earn much less for the same amount of work compared to regular workers.

The government is looking to address this issue by getting non-regular workers’ salaries more in line with their permanent counterparts, though it is unlikely to lead to significant wage increases given that the sectors that employ the most non-regular workers have little productivity and thin margins, and so little room for wage increases.

What can be done?

Understanding that cultural aspects play a key role in preventing wages from rising despite record low unemployment tells us which solutions may work and which may not. Cultural values tend to be deeply ingrained in people’s mindset; as such, any policy that aims to motivate workers into changing their behavior in the workplace is doomed to fail, at least for the foreseeable future.

Providing incentives such as tax deductions to companies that increase wages would mean that companies pay less taxes but more wages. This would require the amount of tax savings to be higher than the additional wage costs to provide any meaningful incentive (otherwise companies lose out as this represents a net cost to them). This would essentially result in the government subsidizing wage increases, something that would come at a significant cost: given a working age population of 76 million and a median annual income of US$ 27‘000, a 2% salary increase would represent a US$40 billion cost to the government.

The only way to get any meaningful result, I think, is to force salaries to go up.

One way to do it is to increase the minimum wage, which is what the government did in 2016 when it raised it by 3%. Japan has one of the lowest minimum wages within developed economies as compared to the median wage. A high minimum wage often leads to higher unemployment, though this is unlikely to happen in Japan given the large number of jobs available. As most of the jobs paying the minimum wage have low qualifications, increasing that minimum wage may accelerate the automation of low-qualified jobs in a country which is highly receptive to new technologies. Still, it is probably a step in the right direction.

A more radical (and effective) solution would be to simply force companies to increase wages by a certain rate each year, say 2 or 3%, for both the public and the private sectors. Each year the government would asses the situation and decide what rate is appropriate. There should be as few exceptions to the rule as possible.

This would come at a cost to employers. But over time, with workers spending more as they earn more, the overall impact on the Japanese economy should be positive. Besides, with the Bank of Japan pumping enormous amounts of money into the economy at zero or negative interest rates, most large Japanese firms are awash with cash and should not suffer significantly from a wage increase imposed by the government.

This is different from indexing salaries to inflation. Doing so provides less flexibility: wage increases cannot be decided each year, they have to rise by the prevailing inflation rate. Inflation-indexed wages often trigger a wage-price spiral that ultimately leads to hyperinflation, as was the case in Brazil in the 1970’s. Although it is very unlikely that Japan would end up in such a situation, indexing salaries to inflation deprives policymakers from the flexibility of deciding by how much wages should increase each year.

Bold action required

For the Japanese economy to start growing again, consumer prices have to rise. Massive creation of money by the central bank has (so far) not resulted in higher inflation: Japanese banks and corporates prefer to sit on large cash reserves rather than invest those funds into the local economy. Despite record low unemployment, wages have not increased, given the unwillingness of most workers to search for higher-paying jobs and request higher wages. None of the various policies over the past 25 years aimed at lifting wages or prices has produced any meaningful result.

The unique characteristics of the Japanese labor market mean that market forces alone will not change workers’ mentalities. Forcing companies to raise wages in the hope that workers who earn more will spend more is a radical but, in my view, viable solution. Even if it fails to prop up prices, it would at least raise wages.

Shinzo Abe’s government together with the governor of Japan’s central bank have enacted a number of daring policies over the years in an attempt to finally break the deadlock that the country finds itself into; they would do well to apply a similar bold approach to wages.

2 thoughts on “Why are wages in Japan not increasing?”